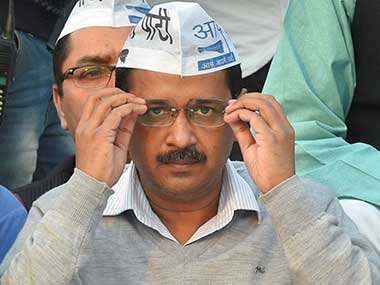

File image of Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal. PTI

File image of Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal. PTISo, why is just Delhi the target of the Election Commission?

Does the law say having parliamentary secretaries is fine for the BJP and the Congress, in Arunachal Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chattisgarh, even in Delhi under Diskshit, but not under Kejriwal?

How does the legitimacy of parliamentary secretaries change with geography, with the party ruling a state?

On any other day, under different circumstances, the Election Commission would have been expected to impartially answer these questions.

It would have been responsible for applying the extant law without any bias or prejudice. But, the manner in which the AAP legislators have been disqualified without a proper hearing, with so much opacity and secrecy, on the final working day of the outgoing chief election commissioner, leaves the questions unanswered.

At stake here is not just the fate of the AAP legislators disqualified by the Election Commission (EC). The bigger question here is can the poll panel apply a law selectively depending on the prevailing political equations? The fundamental question that needs to be addressed is about the impartiality of an institution that is at the vanguard of our democracy.

It is for this reason the fight for Delhi is not just political, which, going by the prima facie iniquitous treatment of the AAP government by the Centre and the history of face-offs with the BJP, it is. The issue of the disqualification of AAP legislators need to be addressed legally too. The valid questions that arise because of the EC decision need to be addressed by our courts. And they need to do so fast to ensure Indian democracy has the same set of rules for every player. To guarantee that every crime, if any, deserves the same punishment, with equal alacrity and severity.

There is no doubt that Kejriwal's intention was not sincere while appointing 21 MLAs as secretaries to assist ministers. In doing so, he was trying to circumvent the constitutional cap on the number of ministers. For a chief minister who won an election on the promise of cleaning up the system, this circumvention of law was a moral and ideological crime. So, in a way, the ongoing troubles for his government are deserved karma.

Yet, Kejriwal's moral and ideological lapses are politically understandable because he has precedence to back him.

His was not the first government to appoint parliamentary secretaries. Nor did his political and legal troubles discourage the BJP to continue with the practice in other states. That's precisely why the punishment sounds harsh, unwarranted and hasty. Ideally, the Delhi high court's decision to declare the appointments null and void ab initio should have been enough rebuke.

The problem here is this: By escalating the issue and that too by allegedly violating principles of natural justice, the EC has put Kejriwal in a slot he loves, that of a victim. Left to himself, Kejriwal would have gone into the next election on the basis of his performance. There is every chance the constant friction within his ranks would have considerably weakened him. But, now he has the advantage of hitting the ground like a cornered victim of an unjust polity.

It is difficult to understand what the Congress and the BJP would achieve with the mini election in Delhi. The Congress, in spite of its bluster and propaganda, is down and out. Maken may be impatient to reclaim lost ground in Delhi but, in case elections are held, he is likely to get a rude shock.

Unless the BJP is relying on an Arunachal Pradesh like coup within the AAP, its gains too would be limited, even self-defeating for three reasons. One, the Delhi voters may be biased but it would be hard to convince them why an unnecessary mini-poll has been foisted upon them by selectively targetting Kejriwal. Two, except among hardcore BJP voters, Kejriwal and his team would arouse sympathy, a factor that could be decisive in an election. Three, it would once again put Kejriwal on the centre-stage, a slot he had been made to relinquish since the debacle in Punjab.

The BJP might be hoping to gain a few seats in case elections are held for these 20 seats. But, the question it needs to answer is this: What will it lose if the courts overturn the decision. Or, if Kejriwal manages to win back most of the seats by playing the victim card?

If that happens, both BJP and Ajay Maken would have embarrassing entries on their CVs.